Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe to TECHEDTV RSS | More

An operating system (OS) is the fundamental software that acts as an intermediary between computer hardware and user applications. It manages hardware resources such as the CPU, memory, storage, and input/output devices, while providing essential services like process scheduling, file management, security, and user interfaces. Without an OS, users would need to interact directly with hardware, which is impractical for most tasks. Common examples include Microsoft Windows, which focuses on graphical user interfaces and broad hardware compatibility; Linux, known for its open-source nature and use in servers; and macOS, optimized for Apple hardware with emphasis on user experience and integration. Operating systems can be monolithic (where all components run in a single kernel space, like traditional Linux) or microkernel-based (where services run in user space for better modularity and reliability, like in Minix). They also handle multitasking, allowing multiple programs to run simultaneously, and provide abstractions like virtual memory to make programming easier.

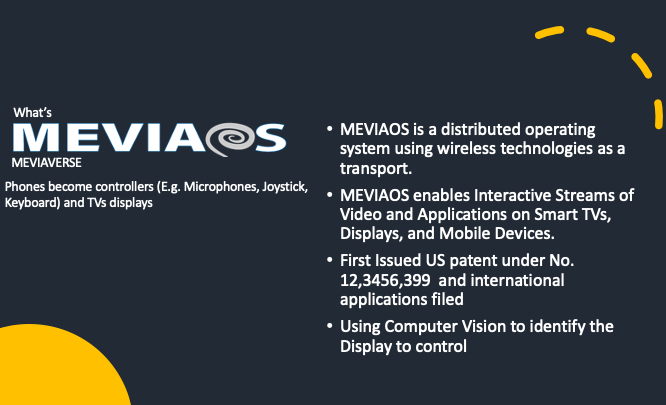

I will first introduce traditional operating systems and its use in current desktops, mobile devices, and servers, and will compare them with my vision for distributed operating systems, as my proposal is MEVIA OS. The main use case is a world of AI agents (e.g. OpenClaw), more decentralized and operating 24/7, requiring then access, configuration, and communications with humans, anytime, anywhere for decision making and final touches as we free our time from being in front of our laptops.

Comparing Traditional Operating Systems

There are three main traditional Operating Systems: Windows, Linux, and MacOS. Their architectures are as follows:

Windows

Microsoft Windows, first released in 1985 as Windows 1.0, evolved from MS-DOS as a graphical extension to provide a user-friendly interface for personal computers. Developed by Microsoft, it quickly became the dominant OS for desktops and laptops due to its compatibility with a wide range of hardware and software. Over the decades, versions like Windows 95 introduced the Start menu and internet integration, while Windows XP (2001) emphasized stability and multimedia. Modern iterations, such as Windows 11 (2021), focus on cloud integration, AI features like Copilot, and enhanced security with features like Windows Hello. Its history reflects Microsoft’s strategy of backward compatibility, ensuring legacy applications run on new versions, which has contributed to its market share exceeding 70% in desktop OS usage as of 2023.

Windows operates on a hybrid kernel architecture, blending monolithic and microkernel elements for efficiency. The NT kernel, introduced in Windows NT 3.1 (1993), handles core functions like process management, memory allocation, and hardware abstraction. It runs in kernel mode for privileged operations and user mode for applications to prevent crashes from affecting the system. The OS supports multitasking through preemptive scheduling, allowing multiple processes to run concurrently. User interaction occurs via the graphical shell (Explorer.exe), with subsystems like Win32 for API calls. Security features include User Account Control (UAC) and BitLocker encryption, while updates are managed through Windows Update for ongoing improvements and patches.

- Kernel: Manages hardware resources, process scheduling, and memory; hybrid design for performance.

- Process Scheduler: Handles multitasking and priority-based execution of programs.

- File System (NTFS): Supports large volumes, encryption, and permissions for data management.

- Device Drivers: Interfaces with hardware like printers and GPUs via the Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL).

- User Interface (GUI): Includes Desktop, Start Menu, and Taskbar for intuitive navigation.

- Security Subsystem: Features like Windows Defender and firewall for threat protection.

- Networking Stack: Manages TCP/IP, Wi-Fi, and cloud services integration.

Linux

Linux originated in 1991 when Linus Torvalds created a free, open-source kernel as an alternative to proprietary Unix systems. Inspired by Minix, it was released under the GNU General Public License, fostering community collaboration. Distributions (distros) like Ubuntu (2004) and Fedora bundle the kernel with tools from the GNU project, making it accessible for servers, desktops, and embedded devices. Its history highlights adaptability, powering over 90% of cloud servers and supercomputers by 2023, thanks to contributions from companies like Red Hat and Canonical. Linux’s philosophy emphasizes modularity, stability, and customization, appealing to developers and enterprises.

Linux uses a monolithic kernel where all core services run in kernel space for speed, though modules can be loaded dynamically. It boots via init systems like systemd, managing services and hardware detection. Processes are scheduled using algorithms like Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) for efficient resource allocation. File systems such as ext4 provide robust data handling with journaling for crash recovery. The OS supports multiple users through permissions and supports shells like Bash for command-line interaction, with graphical environments (e.g., GNOME, KDE) optional. Networking is built-in with tools like iptables for firewalls, and package managers (e.g., apt, yum) simplify software installation.

- Kernel: Core monolithic structure handling CPU, memory, and I/O; supports loadable modules.

- Process Management: Includes scheduler for multitasking and init/systemd for service control.

- File System (ext4, Btrfs): Manages storage with features like snapshots and error correction.

- Device Drivers: Integrated into kernel or as modules for hardware support.

- Shell/User Interface: Command-line (CLI) via Bash/Zsh; optional GUIs like X Window System or Wayland.

- Security Modules: SELinux or AppArmor for mandatory access control.

- Networking: Robust stack with support for protocols, VPNs, and server configurations.

macOS

macOS, formerly OS X, traces its roots to 1984’s Macintosh System Software but was revolutionized in 2001 with OS X 10.0, based on NeXTSTEP acquired from Steve Jobs’ NeXT. Developed by Apple, it integrates tightly with Apple hardware for optimized performance. Key milestones include macOS Sierra (2016) with Siri integration and macOS Ventura (2022) emphasizing continuity features like Universal Control. By 2023, it holds about 16% of the desktop market, prized for creative professionals due to its Unix-like foundation and ecosystem synergy with iOS. Its history underscores Apple’s focus on user experience, security, and innovation.

macOS employs a hybrid kernel called XNU, combining Mach microkernel for messaging with BSD Unix for POSIX compliance. It runs on Darwin, an open-source base, managing resources efficiently on Apple Silicon (M-series chips since 2020). The Aqua interface provides a polished GUI with gestures and animations, while Core Services handle tasks like file sharing. Multitasking uses Grand Central Dispatch for parallelism, and security features Gatekeeper and XProtect. App management occurs via the App Store, with seamless iCloud integration for data syncing across devices.

- Kernel (XNU): Hybrid with Mach for inter-process communication and BSD for Unix compatibility.

- Process Scheduler: Manages threads and priorities using Grand Central Dispatch.

- File System (APFS): Supports encryption, snapshots, and fast cloning for data efficiency.

- I/O Kit: Framework for device drivers, ensuring hardware integration.

- User Interface (Aqua): Includes Dock, Mission Control, and Spotlight for search.

- Security Framework: Features like FileVault, SIP (System Integrity Protection), and privacy controls.

- Networking: Built-in support for AirDrop, Bonjour, and internet protocols.

Distributed Operating Systems

A distributed operating system extends the concept of a traditional OS across multiple networked computers or devices, making them appear as a single, cohesive system to the user. Unlike a standard OS confined to one machine, a distributed OS coordinates resources (e.g., processing power, storage, memory) over a network, enabling fault tolerance, scalability, and load balancing. Examples include historical systems like Amoeba (developed at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, which treated a cluster of machines as one entity with shared processes) or Plan 9 from Bell Labs (which distributed file systems and namespaces across networks). Modern equivalents can be seen in cloud platforms like Kubernetes, which orchestrate containers as if they were part of a unified OS. Key challenges in distributed OS include network latency, data consistency, and synchronization, often addressed through protocols like remote procedure calls (RPC) or message passing.

MEVIA OS: A Distributed Operating System

MEVIA OS, as detailed in US Patent 12346399B2, is a distributed operating system designed to enable seamless, web-based interactions across heterogeneous devices, primarily using mobile devices (e.g., smartphones or tablets) as controllers and smart televisions or other displays as output devices. It operates through a Device Connect Platform (DCP), which serves as the core middleware, handling messaging, streaming, and computation in cloud-based or decentralized environments. This setup allows for real-time control of web applications on remote displays without requiring native software installations, leveraging standard web technologies like HTML, CSS, JavaScript, WebSockets for bidirectional communication, and WebRTC for peer-to-peer media streaming.

The following figure shows how different applications are routed and messages passed from one application to the displaying application in a decentralized way.

Key components and functionalities include:

- Controllers and Interfaces: Mobile devices emulate various input devices (e.g., game controllers, keyboards, cameras, microphones, or 3D gesture recognizers) via browser-based interfaces loaded from URLs. Inputs like touches, swipes, or accelerometer data are captured using libraries such as gestures.js and converted into JSON messages (e.g., {evt: ‘touchstart’, x: 100, y: 200}) for transmission.

- Displays and Rendering: Smart TVs or similar devices run web applications modified with mevia.js to receive and process these inputs, updating content in real-time. Tools like FFMPEG and Puppeteer handle screen capture and adaptive streaming (e.g., HLS, RTMP) for compatibility with limited-browser devices.

- Content Routing and Synchronization: A central content router uses Application IDs (AppIDs), UUIDs, and QR codes for device pairing and event mapping. It translates raw events into JavaScript commands or emulates hardware (e.g., USB devices over IP using USBIP) for cross-platform support.

- Advanced Features: Includes neural network-based gesture recognition (e.g., LSTM models for 3D motions), Ultra-Wide Band (UWB) for proximity detection, and integration with legacy systems like Windows via message routing. Authentication supports biometrics, certificates, or payments, while STUN/TURN servers handle network traversal.

The system supports applications like gaming, video conferencing, drawing, and streaming services (e.g., controlling Netflix from a phone), with QR code scanning enabling quick setup. It also extends to broadcast integrations like ATSC 3.0 or cable TV, allowing interactive experiences.

Comparison of Traditional Operating Systems to MEVIA OS

In essence, while traditional OSs excel in standalone environments, MEVIA OS innovates by creating a unified, browser-driven distributed system tailored for interactive, multi-device use cases like smart home entertainment or remote collaboration, addressing gaps in legacy protocols and enabling greater flexibility through web technologies.

Decentralized Operating Systems and Their Suitability for a World of AI Agents

Decentralized operating systems (DOS), as MEVIA OS, represent a shift from traditional, centralized OS like Windows or Linux, where control and resources are managed from a single point. Instead, DOS distribute computing power, data storage, and decision-making across a network of nodes, often leveraging blockchain, peer-to-peer protocols, or edge computing. This architecture eliminates single points of failure, enhances scalability, and promotes autonomy among connected devices or agents. Examples include Autonomos, built on the Base blockchain for robotics and IoT, or ElizaOS, designed specifically for deploying autonomous AI agents. These systems enable seamless collaboration in distributed environments, making them ideal for emerging technologies like AI agents that require real-time interaction, data sharing, and resilience.

In a “world of agents,” AI entities operate autonomously or semi-autonomously to perform tasks, make decisions, and interact with humans or other agents. This paradigm, often called agentic AI, envisions networks where agents handle complex workflows, such as in multi-agent systems (MAS) that distribute problem-solving without central control. Decentralized OS are more suitable here because they provide the infrastructure for agents to run independently yet collaboratively, ensuring fault tolerance (if one node fails, others continue), efficient resource allocation through distributed computing, and enhanced security via decentralized data handling. For instance, in agentic organizations, this leads to flat, outcome-focused networks where agents integrate across systems using protocols like an AI mesh. Compared to centralized OS, which can bottleneck scalability and introduce vulnerabilities, DOS support dynamic, self-optimizing agent ecosystems, as seen in platforms like Scale Computing for edge-based agentic AI.

OpenClaw as an Example in an Agentic World

OpenClaw, an open-source autonomous AI agent (formerly known as Clawdbot and Moltbot), exemplifies the kind of intelligent entity that thrives in a decentralized OS environment. Launched in late January 2026, it runs locally on a user’s machine as a persistent assistant, integrating with messaging apps like WhatsApp, Telegram, Slack, or Discord to execute tasks such as sending emails, automating browser actions, managing calendars, running shell commands, and even self-improving by writing new code skills. It connects to large language models (LLMs) like Claude or GPT for reasoning and operates via a heartbeat scheduler for proactive, unprompted actions, making it a true agentic tool with over 100,000 GitHub stars shortly after release. However, its local-first design raises security concerns, such as potential exposure if misconfigured, allowing adversaries to commandeer it as a backdoor.

In a world dominated by such agents, decentralized OS like MEVIA OS, DeAgentAI or those supporting distributed agent networks are more suitable for OpenClaw-like systems because they enable seamless scaling across devices without relying on a central server, which could limit autonomy or introduce latency. For example, agents could collaborate in real-time via shared memory layers or federated learning, as in decentralized AI platforms, ensuring privacy through localized data processing and reducing risks like those in OpenClaw’s exposed instances. This contrasts with traditional OS, where agents might face integration hurdles or single-point vulnerabilities; DOS foster a resilient, user-sovereign ecosystem where agents like OpenClaw can operate freely, sustainably, and securely in multi-agent setups.